I moved back to India from London a little over two years ago to lead Pocket FM’s Design. The story didn’t begin in a boardroom; it began in a hospital. This is a reflection on that shift, from leading a few people to carrying responsibility for an entire team. Along the way, I kept asking myself: Was I prepared? Was it the right decision? What did it cost, and what did it teach me?

It began on a hospital bed after an accident in Boston.

At the time, life was at one of its most exciting phases. I was working at Meta, planning a move from London to San Francisco, ready to work on things I genuinely cared about. But life rarely moves in straight lines. A lot was already unfolding back home. My mind was torn between London and Dehradun, between ambition and responsibility. On top of that, there was the usual internal noise that comes with transitions.

I was in New York to meet members of what would have been my new team. After that, I decided to visit a close friend at Harvard. That’s where the accident happened. Suddenly, everything stopped.

I needed major surgery. Waivers to be signed by my family. And waiting just to find out if a surgery slot would open up at a Massachusetts General Hospital for the week, since it was a nose injury, it needed to be operated on within 7 days. This happened on a Sunday. By Monday, I was told there were no surgery slots available for the week. I was advised to go back to London, where I was based at the time.

I’m deeply grateful to Meta’s emergency response team. They stepped in and handled everything. The next day, I took the flight loaded with painkillers and a fully patched-up face because my nose had ruptured on one side. At that time, I didn’t even feel like I had a face.

Somewhere mid-flight, a very simple thought hit me. What is the point of all this if, at the moment I need my family the most, I’m completely alone?

I had experienced the NHS (National Health Service, UK) before. I had little faith, and more importantly, I wanted to be close to my family. While still on the flight, I began checking tickets to India. I found an Air India flight leaving just a few hours after I landed in London. I booked it. I landed at Gatwick airport, went home, dropped my bags, picked up a few essentials, and headed straight to Heathrow. There was plenty of drama at the Air India check-in. They didn’t want to let me board given my condition. That’s a story for another day. Eventually, I boarded the flight and flew back to India.

My family was waiting at the airport. We went to the hospital the same day. I got a surgery appointment for the very next day. Within 24 hours of landing in India, the surgery was done. In contrast, there were no slots in the US and a big question mark in the UK.

That moment quietly reframed how I think about responsibility, not as ambition, but as proximity to what actually matters. That contrast stays with you.

While recovering in the hospital, boredom kicked in. And if you know me, I’m a bit of a restless being, who wants to create most of the time; boredom led to curiosity. I started looking at what was happening in the Indian tech scene. I began speaking to a few founders working on interesting, messy, unresolved problems.

I love working in grey areas. Places where things aren’t fully defined yet, where the playbook doesn’t exist. (One of the reasons I started my research in AR/ VR interfaces back in 2017). That same curiosity led to conversations with Rohan Nayak, co-founder of Pocket FM. There was no agenda. Just curiosity. I talk to people to learn, that’s always been my default.

At that point, I was seriously considering a sabbatical. Since the day I started working, it has been a straight line. Work, study, work. No real pause. I went back to London after recovery, decided to resign, and planned to figure out what was next.

Somewhere along the way, between conversations with all co-founders and looking closely at the problem Pocket FM was trying to solve, I dropped the sabbatical plan. The problem felt real. The scale was real. More than anything, it felt like a problem worth carrying, not postponing.

I left Meta, moved my life back to India by the end of November 2023. Just a couple of days after moving back, I flew to San Francisco to deliver one of my major talks, presenting my ideas on Spatial Typography at Stanford, and then I came back to India. The following week, I joined Pocket FM in December 2023.

That’s where this chapter really began.

When I joined, the brief was clear. Pocket FM was growing rapidly in the US, but from a design and experience perspective, it didn’t feel global. The challenge was to go head-to-head with the biggest players in the industry. One recommendation on the table was to rebuild the team from scratch.

I don’t believe people want to do bad or subpar work. Most people want to do their best. The real question is whether the system around them allows that. Recognising people’s potential and helping them grow is something I strongly believe in. That belief shaped everything that followed.

Phase 1: Setting frameworks, shared understanding and clean-up

Phase one was less about design output and more about earning the right to lead. One of the hardest decisions I took early on was to stop the design system work that was already in progress. It was half-built, and more importantly, it wasn’t original or strong enough to compete globally.

This meant months of work being thrown away. I was relieved to see strong alignment from the founders. We consciously chose quality over sunk cost. This phase was about understanding the existing team, the environment, and the system they were operating in. And this is where my belief was reinforced. The issue wasn’t the people. It was the system. Work is often a by-product of the environment. To understand any output, you first have to understand the system that produces it.

What followed was six months of intense mentoring and upskilling. Hours of hands-on work. Not just to raise the bar, but to make the bar visible. Most of the people from that phase are still part of my team, and that’s something I’m proud of.

This was new territory for me, too. I had led people before, but not at full capacity. Being an IC is comparatively simple. You focus on the work. Management carries a different kind of load, and it does take a toll, more on it some other time.

Rulebooks tell people what to do.

Frameworks guide people on how to act.

Rulebooks insist on discipline.

Frameworks allow for creativity.

– Simon Sinek

During this phase, I had setup system and frameworks so that things become transparent for everyone and there is no room for bias. Defining clear expectations for every level, roles and responsibilities for designers was clearly defined so that they can self-benchmark themselves and identify growth areas. This clearly reduces the issues of people not being clear about their growth path and the all-too-common randomness in growth conversations within the Indian design industry. Note: In my team, the number of years doesn’t define your level; your work does.

This phase was intense. I was shaping the micro-culture of the design team within the org. We went through forming, storming, and norming. There was a fair amount of storming with product managers and their leaders, not out of bitterness, but out of alignment.

Good design doesn’t happen in a couple of hours. If you want quality and innovation, you have to allow time for thinking. Execution-only environments kill both.

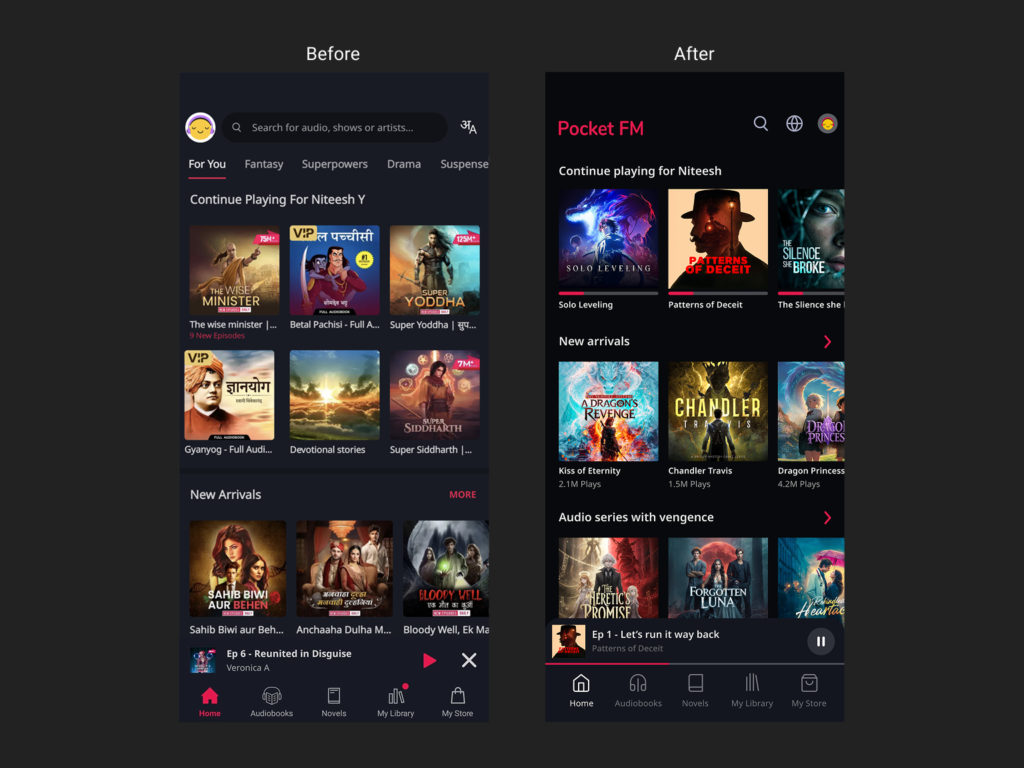

During this phase, we spent time cleaning up the apps Pocket FM and Pocket Novel, just to make them look presentable. It was a design-led initiative where designers identified all the issues and how to fix them. This was a good shared exercise for them to start understanding the nuances and details of design that bring quality to the product. This was a hands-on period for me to work with the team and set the tone for the future.

As I summed it up to the team at the time:

We acknowledged that our design hygiene was off. The app didn’t reflect the team we wanted to be, and there was little to be proud of. So we rolled up our sleeves. We cleaned up the mess, took stock of where we stood and built a first layer of stability across screens, teams and expectations.

Phase 2: From foundation to language

Once the basics were in place, it was time to level up. We shifted our focus from a design system to a design language. A language that reflected who we were as an organisation and what we stood for. It began as a vision deck I presented to the founders.

The core idea was simple. Stay true to our roots. Pocket FM is an audio-first product. From a design perspective, that meant visualising sound. That idea became the backbone of our manifesto and guiding principles. Once those were clear, we began building the design system. That’s how the Aural design system was born. We call it Aural Symphony.

At this stage, we weren’t a full design function yet. We were still a team of designers. So I hired our first UX researcher and content designer. We wanted our work to be grounded in user insight, not just instinct. This was also the phase where we started hiring fresh talent and building momentum.

The design system work was intense. To give you a sense of it, the button alone went through upwards of 50+ iterations. Different directions, different philosophies. We finally landed on a design inspired by illuminated buttons on audio devices.

Every component reflected our core principles. One example is how we treated shapes. Rounded elements signal interaction. Rectangular ones signal static content, with a few deliberate exceptions. Motion and haptics became central to the system. We shipped the design system in two months. Execution, however, was a different story. This wasn’t a simple visual update. It required full-revamp of the code architecture. And when your app serves millions of users, nothing is straightforward. We started with limited betas, tested extensively, fixed what broke, and made some hard calls along the way.

It took months of iteration before we reached a full rollout.

Throughout the period, we kept collecting feedback and the reception to the new design system was better than I imagined. And it was a testament of what our team had created, something that everyone was proud of. That was the first time I felt the team wasn’t just executing my direction, but owning a shared identity.

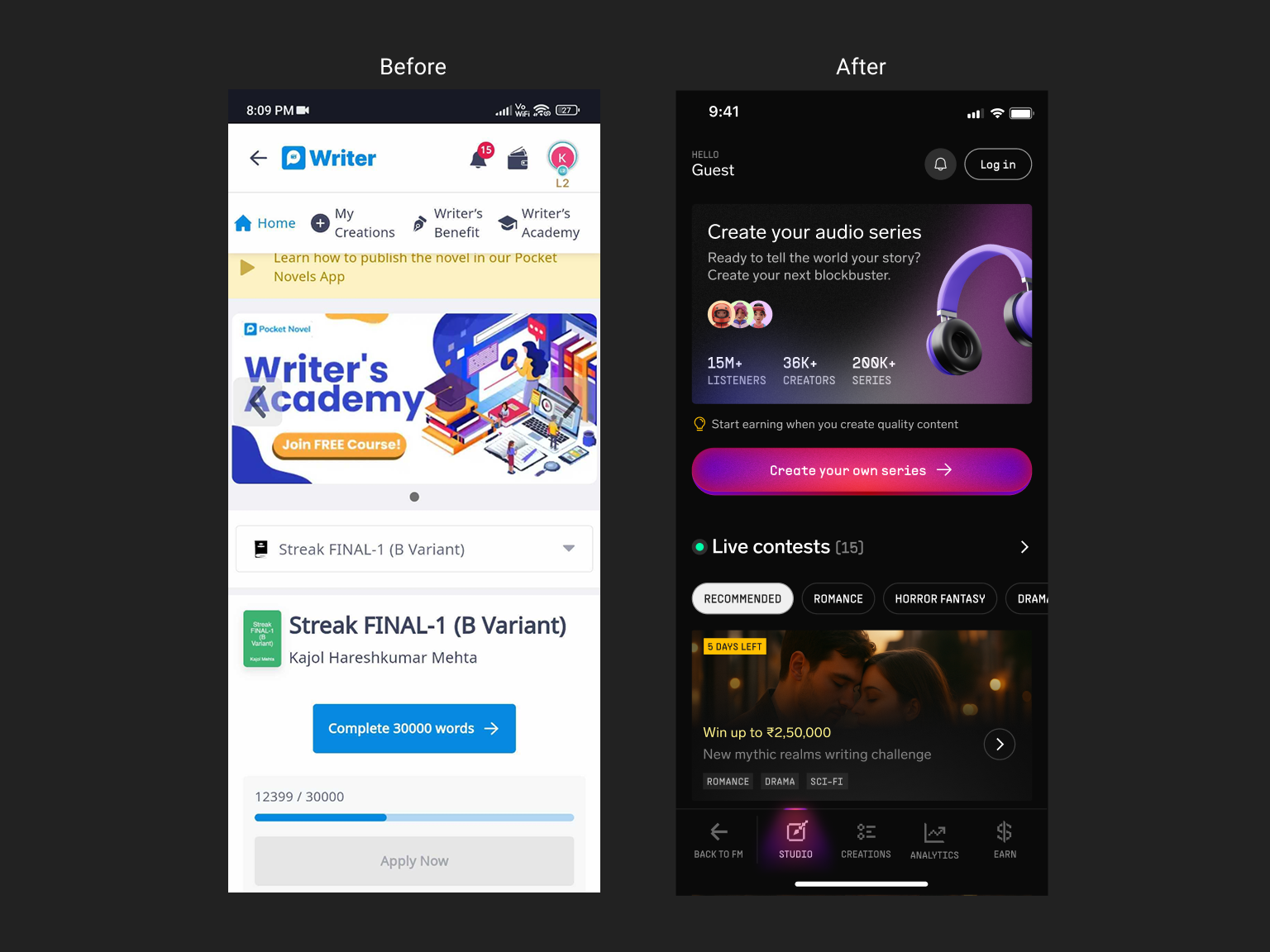

One of the things I’m most proud of is that this attention to detail wasn’t limited to the customer-facing experience. We applied the same care to internal products and experiences serving smaller, often invisible user groups, especially our writers. Many of them had never used a desktop before. They started writing on their phones. These weren’t typical tech-savvy users, but people from tier-3 cities, and often homemakers, discovering a new form of creative expression through writing.

By this point, design had moved beyond execution. It became an embedded function. Cross-functional trust grew. Research started shaping product direction. Design stopped being a coat of paint at the end. We weren’t chasing tasks anymore. We were solving problems.

The question then shifted from building stability to preventing comfort from quietly becoming complacency.

Phase 3: Raising the bar again

A more mature team. A stronger foundation. Higher expectations.

This phase is about going beyond “good enough”. Thinking strategically. Collaborating deeply. Delivering work that doesn’t just solve today’s problems, but defines new ones.

We kicked this off in July 2025. And this is what I wrote to the team.

I began this reflection asking whether I was prepared, whether it was the right decision, and what it cost me. Some of those answers are clearer now, the rest deserve their own space, and I’ll come back to them soon.

PS. How I lead is shaped by a fair share of both great and difficult managers. Each taught me something I’m grateful for. How I lead is a byproduct of those experiences: what truly motivated me, and what quietly pulled me down.

Everything I’ve been able to do rests on the shoulders of my team and the people I’ve had the chance to work with.